Thus, the horizon would no longer be reliably straight, and the sun and moon would swing wildly through the sky depending on one’s position.” A visitor to R’lyeh, he says, would “see the outside world (and other distant objects upon the island) as if through a large fishbowl. In a region of curved spacetime, Tippett explains, light doesn’t travel in reliably straight trajectories, so objects beyond the curved region appear warped and skewed, and the relative positions of two objects, or the flatness of a large object, in the region are difficult to discern. R’lyeh, he says, lies in a “region of anomalously curved spacetime,” and the bizarre geometry of the buildings and changing alignment of the horizon are the consequences of the “gravitational lensing of images therein.”

In the process, he sort of becomes a Lovecraftian narrator himself, a scholarly man digging a bit too far into forbidden knowledge on his way to developing what he calls a “unified theory of Cthulhu.”Īfter poring over the clues and descriptions left by Lovecraft’s characters and employing his “mad general relativity skills,” Tippett thinks that the geometry of R’lyeh was all wrong-not because the architecture curves and angles in strange ways, but because of the space the city occupies. Tippett isn’t shy about pulling out the Lovecraftian adjectives and cites the various letters and documents that drive “The Call of Cthulhu” like another scientist might reference previous research.

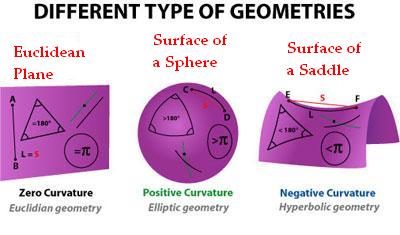

His playful paper, “ Possible Bubbles of Spacetime Curvature in the South Pacific,” is a lot of fun and reads like a mashup of a standard science paper and one of Lovecraft’s own stories. If it was, though, would science be able to explain the weird geometry of the city? Benjamin Tippett, a theoretical physicist and mathematician at the University of New Brunswick, gave it a shot. Of course, none of it-the sailors, the city, the island, the dead-dreaming god-are real. Even when they discover a simple door, the sailors couldn’t tell if it “lay flat like a trap-door or slantwise like an outside cellar-door” because the “geometry of the place was all wrong.” “One could not be sure that the sea and the ground were horizontal, hence the relative position of everything else seemed phantasmally variable,” one of the sailors, Gustaf Johansen, wrote in his log. Exploring the island, the sailors soon discover that “all the rules of matter and perspective seemed upset,” and they struggle to comprehend and describe their surroundings. In “ The Call of Cthulhu,” Lovecraft’s most famous story, a crew of sailors accidentally discover a risen part of the city, an island with a “coast-line of mingled mud, ooze, and weedy Cyclopean masonry,” accidentally wake Cthulhu from his sleep, and are either killed or driven mad.Įven if you ignore the monstrous god waiting in its vaults, the architecture and landscape of R’lyeh are enough to test one’s sanity. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos, somewhere sunken in the South Pacific there is a “nightmare corpse-city” called R’lyeh, “built in measureless eons behind history by the vast, loathsome shapes that seeped down from the dark stars.” In his house in this city, the great old god Cthulhu waits, dead and dreaming, for his return to power.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)